Do lobsters feel pain? Is it cruel to eat crabs? In this blog, we explore the lives of the crustaceans captured for food.

Recent studies show that lobsters, crabs and other decapod crustaceans used for food do have nervous systems and can feel pain.

Whether they are cut, boiled alive or mutilated in other ways, these overlooked animals suffer immensely in order for humans to eat them.

Despite being captured in huge numbers, crustaceans remain unprotected by animal welfare laws around the world. In the UK alone, around 3,000 tonnes1 of lobsters are caught and a staggering 721,000 metric tonnes2 of crabs are sold every year.

How are lobsters and crabs caught?

The most common method used by UK fisheries is called potting, which involves placing baited pots to trap animals such as crabs, lobsters and crawfish.

They enter the pots to collect the bait and are prevented from escaping, but smaller, non-target species can escape and return to the sea.

After the pots fall to the seabed, they can be left for anything between a few hours to several days before fishing boats retrieve them.

In the UK, there is no limit on lobster catch, leading to a considerable risk of overfishing. According to the Marine Conservation Society3, there are gaps in data for crab and lobster stocks in the Irish Sea, the eastern English Channel and Scotland, making it difficult to determine whether species are overfished or not.

However, the available data show that the majority of lobster and brown crab populations are lower than is healthy, and that general fishing levels are above what is considered to be sustainable.

Learn more about how modern fishing methods harm the environment.

How are they transported and stored?

The cruel methods of transport and storage are seriously harmful to animals like lobsters, crabs, prawns and crayfish who are extremely vulnerable to drastic changes in temperature and being exposed to air.

They are tightly packed in transport crates alongside many others, which is unnatural for solitary animals who prefer the open space and are known to be territorial. Those crammed in the bottom of the storage crates are at an increased risk of losing limbs and suffocation.4

As well as being stripped of the ability to express their natural behaviours, they suffer from hunger and dehydration during this traumatic process.

According to research, crabs can have their claws bound during storage, severely restricting movement and resulting in muscle loss. Some crabs may be stored in these conditions for months.5,6

Declawing and mutilation

Crabs caught for human consumption are manually declawed for people to consume the flesh within them, a stressful experience that increases mortality. 7,8 Research also shows that declawed crabs are aware of their wounds and may try to tend to them, indicating their ability to feel pain.9

In the UK, it is legal for crabs to be released back into the sea after declawing so their claws can regrow, but evidence shows that this affects their welfare, prevents them from feeding themselves effectively10 and hinders their ability to defend themselves against predators.11

Do lobsters feel pain when boiled alive?

Recent scientific studies have proven that lobsters do more than simply react to unpleasant stimuli (this is called nociception). There is growing evidence to show that lobsters and other crustaceans do feel pain like other animals and should be considered sentient.

When live lobsters are plunged into a pot of boiling water, their tails twitch and they will desperately try to escape, indicating that this is a painful and terrifying experience for them.

Lobsters produce the hormone cortisol,12 the same hormone humans produce when hurt. Research also shows that lobsters can be alive for up to three minutes13 after being thrown into the boiling water.

One study14 involved researchers setting up two shelters for shore crabs – one gave the crabs an electric shock, while the second shelter was safe. Crabs who remained in the first shelter would be shocked again the longer they remained there.

The researchers saw that the crabs were more likely to choose the safe shelter and stay there, suggesting that the crabs aren’t merely reacting to stimuli; they can remember painful experiences and will try to avoid them again in the future.

There are other methods used to slaughter lobsters, such as freezing or stunning before boiling them which are considered more ‘humane’, but the kindest thing to do is to leave these incredible creatures off our plates.

The UK Parliament has revised the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Bill 2022 to include cephalopod molluscs and decapod crustaceans, who are sadly overlooked and forgotten all too often. Boiling lobsters alive is already illegal in Norway, Switzerland and New Zealand and we hope to see this happen in the UK and the rest of the world.

What are the alternatives?

The verdict is in: fish feel pain, and so do other aquatic animals including crustaceans.

Crustaceans are unique animals with many fascinating behaviours. Did you know that crabs can communicate by waving their pincers, that prawns may have personalities, or that lobsters can live up to 100 years old? These complex creatures deserve to live their lives naturally instead of being captured and sold as delicacies.

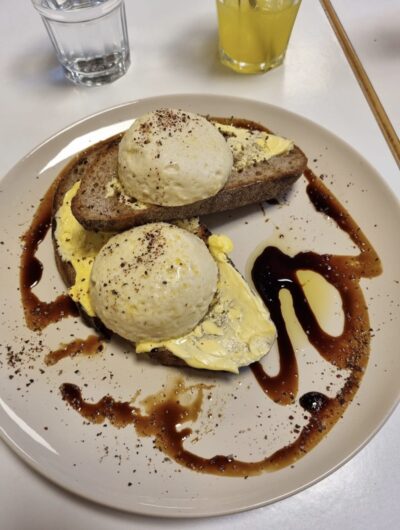

You can make a difference by choosing the growing range of vegan seafood alternatives. It’s never been easier to find delicious swaps, and if you want to get creative in the kitchen, you can make plant-based lobster rolls, prawn chow mein and so much more.

For more support with making plant-based seafood swaps, check out our Choose Fish-Free Campaign.

References

1. The Fish Society (n.d.). A guide to lobster. [online] The Fish Society. Available at: https://www.thefishsociety.co.uk/fishopedia/lobster [Accessed 22 May 2023].

2. Statista (n.d.). Crab: annual sales volume UK 2022. [online] Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/512590/crab-sales-volume-united-kingdom-uk/ [Accessed 22 May 2023].

3. Marine Conservation Society. (n.d.). The lowdown on crab and lobster in the UK. [online] Available at: https://www.mcsuk.org/news/the-lowdown-on-crab-and-lobster-in-the-uk/ [Accessed 22 May 2023].

4. Barrento, S., Marques, A., Vaz-Pires, P. and Nunes, M.L. (2010). Live shipment of immersed crabs Cancer pagurus from England to Portugal and recovery in stocking tanks: stress parameter characterization. ICES Journal of Marine Science, [online] 67(3), pp.435–443. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/67/3/435/733388 [Accessed 22 May 2022].

5. Barrento, S., Marques, A., Vaz-Pires, P. and Nunes, M.L. (2010). Live shipment of immersed crabs Cancer pagurus from England to Portugal and recovery in stocking tanks: stress parameter characterization. ICES Journal of Marine Science, [online] 67(3), pp.435–443. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/67/3/435/733388 [Accessed 22 May 2022].

6. Esposito, G., Nucera, D. and Meloni, D. (2018). Retail Stores Policies for Marketing of Lobsters in Sardinia (Italy) as Influenced by Different Practices Related to Animal Welfare and Product Quality. Foods, [online] 7(7), p.103. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/7/7/103 [Accessed 22 May 2023].

7. Patterson, L., Dick, J.T.A. and Elwood, R.W. (2007). Physiological stress responses in the edible crab, Cancer pagurus, to the fishery practice of de-clawing. Marine Biology, [online] 152(2), pp.265–272. Available at: https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/publications/physiological-stress-responses-in-the-edible-crab-cancer-pagurus- [Accessed 22 May 2023].

8. Patterson, L., Dick, J.T.A. and Elwood, R.W. (2009). Claw removal and feeding ability in the edible crab, Cancer pagurus: Implications for fishery practice. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, [online] 116(2-4), pp.302–305. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168159108002104 [Accessed 22 May 2023].

9. McCambridge, C., Dick, J.T.A. and Elwood, R.W. (2016). Effects of Autotomy Compared to Manual Declawing on Contests between Males for Females in the Edible Crab Cancer pagurus: Implications for Fishery Practice and Animal Welfare. Journal of Shellfish Research, [online] 35(4), pp.1037–1044. Available at: https://pureadmin.qub.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/121336077/effects_of_autonomy_combined.pdf [Accessed 22 May 2023].

10. Patterson, L., Dick, J.T.A. and Elwood, R.W. (2009). Claw removal and feeding ability in the edible crab, Cancer pagurus: Implications for fishery practice. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, [online] 116(2-4), pp.302–305. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168159108002104 [Accessed 22 May 2023].

11. Davis, G.E., Baughman, D.S., Chapman, J.D., MacArthur, D., and Pierce, A.C. (1978). Mortality associated with declawing stone crabs, Menippe mercenaria. South Florida Research Center, [online] Report T-552, 20 pp. Available at: https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/FI/44/44/00/02/00001/FI44440002.pdf [Accessed 22 May 2023].

12. Villazon, L. (n.d.). Why are lobsters cooked alive and do they feel pain? [online] BBC Science Focus Magazine. Available at: https://www.sciencefocus.com/nature/why-are-lobsters-cooked-alive-and-do-they-feel-pain/ [Accessed 22 May 2023].

13. Elwood, R.W. and Appel, M. (2009). Pain experience in hermit crabs? Animal Behaviour, [online] 77(5), pp.1243–1246. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003347209000712 [Accessed 22 May 2023].

14. Magee, B. and Elwood, R.W. (2013). Shock avoidance by discrimination learning in the shore crab (Carcinus maenas) is consistent with a key criterion for pain. Journal of Experimental Biology, [online] 216(3), pp.353–358. Available at: https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/216/3/353/11942/Shock-avoidance-by-discrimination-learning-in-the [Accessed 22 May 2023].