Plant-based milk alternatives like soya, oat and almond have been gaining popularity in recent years, with nearly a third of Brits now choosing them over dairy for ethical, environmental or health reasons.1 This shift has prompted closer attention from public bodies, including a new government report examining the nutritional quality of plant-based milks in comparison to cow’s milk.

Ultimately, the UK Government concluded in their recommendations for the general population that fortified and unsweetened (without free sugars or non-sugar sweeteners) almond, oat and soya drinks are an acceptable alternative to cow’s milk.

Despite their widespread use, there are still concerns from the public about choosing plant milk alternatives. In this blog, we take a closer look at some of these issues to help people make informed choices.

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is vital for the production of red blood cells and supporting the nervous system. Most people in the UK rely on animal products to obtain enough vitamin B12. Meat and dairy are often touted as natural sources of vitamin B12, but this is not strictly true.

Although it is present in animal products, B12 is made by the bacteria inside animals and not by the animals themselves. As modern farming practices involve keeping animals indoors for most of their lives, many farmed animals cannot obtain B12 through the soil and obtain it through supplemented feed instead.2,3

While it takes more planning to get sufficient B12 on a plant-based diet, many plant milks and dairy alternatives are fortified with it. Everyone eating a vegan diet should take a B12 supplement as well as consuming fortified foods to ensure you get a consistent and reliable supply.

Calcium

We’ve all heard that cow’s milk is an essential source of calcium and we need it to build strong teeth and bones. Of course, cow’s milk is a source of calcium, but that doesn’t mean it is the only way we can get it in our diets.

Calcium is available in many plant-based foods and some dairy alternatives are fortified with it.4 If you’re regularly consuming calcium-rich plant foods as well as fortified vegan alternatives, you shouldn’t fall short of this essential mineral.

Look for fortified foods such as calcium-set tofu, plant milk and other dairy alternatives, as well as kale, watercress, tahini, apricots and haricot beans. The Vegan Society recommends including at least two portions of calcium-fortified foods such as tofu alongside other plant-based sources in our diets every day. 5

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is essential for healthy bones, teeth and muscles, and deficiency can lead to conditions such as rickets. Deficiencies in vitamin D are common across the population regardless of diet, and as a result, many everyday foods are fortified, including plant milks and dairy alternatives.

In the UK, people are advised to take a vitamin D supplement in autumn and winter of 10mcg (400 IU) a day.6 For those who don’t spend much time outside or don’t eat foods containing vitamin D, a supplement is sensible all year round.

Vitamin D2 is always suitable for vegans, but vitamin D3 can be derived from animals, so ensure you choose a vegan brand of D3. For more information on vitamin D, check out our dedicated blog.

Iodine

Iodine helps make thyroid hormones, which keep cells and the metabolic rate healthy. There are concerns that people across the population are not getting adequate iodine, regardless of diet.

Cow’s milk and other dairy products are among the most popular sources of iodine in the UK, but they do not naturally contain high amounts. Iodine solutions are used to sanitise milking equipment and the teats of cows farmed for their milk, and cows can also be given iodine-fortified feed.7

Some plant milks are fortified with iodine, but it is not consistent across brands so they may not provide iodine in the same amounts as dairy.8,9 Instead of relying on plant milk for iodine, get it from other plant sources such as seaweed, grains and nuts, or alternatively, take a supplement. Read more about iodine on a vegan diet in our dedicated guide.

Protein

We need protein in our diets for muscle growth and repair, hormone production, energy and much more. Cow’s milk is a source of protein, but there are plenty of plant-based protein sources we can choose, too. Although some plant milks are lower in protein than cow’s milk (such as almond, cashew and oat), you can get a similar amount of protein per 100ml from soya milk, containing all the essential amino acids.

Other vegan protein sources include tofu, tempeh, seitan, beans, peas, lentils, nuts and quinoa. Eating a diverse range of plant foods every day is also beneficial to our gut health, so we can enjoy an array of protein-rich plant foods to meet our protein requirements.

Sugar

Sugar levels can vary significantly between plant milk alternatives as there are lots of different products available. Some plant milks also have naturally occurring sugars – just like cow’s milk does.

While some varieties of plant milks, especially flavoured or sweetened options, usually contain added sugars, many brands offer unsweetened versions with little to no sugar at all. Those looking to reduce their sugar intake can choose unsweetened plant-based milks to enjoy dairy alternatives without added sugars.

Saturated fat

It’s no secret that many animal products are high in saturated fat, which contributes to high levels of cholesterol and increases our risk of developing heart disease. On the other hand, plant-based diets are rich in whole grains, beans, fruits and vegetables, all of which are low in saturated fat and contain no cholesterol.

Full-fat cow’s milk is high in both saturated fat and cholesterol, and while some of these fats can be beneficial for us, it can be worth switching to plant milks if you’re looking to reduce cholesterol and saturated fat in your diet. Plant milks are low in saturated fat and do not contain cholesterol. Whole food plant-based diets have also been linked to lower cholesterol levels and reduced risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes, so it makes sense to include more plant foods in our diets.10

Ultra-processed foods

Are plant milks ultra-processed? That depends. Most foods we buy from supermarkets undergo some form of processing and this doesn’t mean they are ‘bad’ for us – some processes make a food last longer, ensure it is safe for consumption or even improve its nutritional profile.

Dairy alternative products vary widely and it is important to treat this subject with nuance. Some plant-based milks may fall under NOVA’s ultra-processed classification because they have added vitamins and minerals, or emulsifiers to extend shelf life and improve texture. Many plant-based milks are made with just a few simple ingredients such as water, oats or nuts.

NOVA’s definition of UPFs doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story about the nutritional value of a food product and some experts have challenged these classifications.

Lactose

Plant milk alternatives are not simply a preference for some – millions of people worldwide are lactose intolerant and plant-based milks offer a safe alternative to traditional dairy products.11 These people get their calcium and other vitamins and minerals without having to rely on dairy.

People who are lactose intolerant don’t have the enzyme needed to digest lactose – the sugar found in dairy milk – leading to uncomfortable digestive symptoms. Plant-based milk alternatives allow them to enjoy milky beverages without these symptoms.

Plant-based alternatives also open up a world of flavours as there are so many varieties available in supermarkets and cafés. From creamy, barista-style oat milk to the nuttier flavours of almond and hazelnut milk, there’s a non-dairy alternative to suit every beverage and recipe.

Pus

Many cows farmed for their milk suffer from mastitis, a bacterial infection of the udder that causes painful swelling or hardening. This painful infection is frequently attributed to unhygienic, cramped and poorly ventilated living conditions. In a herd of 100 cows, there could be as many as 70 cases of mastitis every year in the UK.12

Cows with mastitis produce more white blood cells to fight the infection which then become part of her milk. These are called somatic cells, which have the appearance of pus. A higher somatic cell count means there is a greater chance that the udder is infected.

With mastitis so prevalent in cows on dairy farms, there is no way to avoid it, and the legal limit in the EU for human consumption of pus is 400,000 cells per litre.13

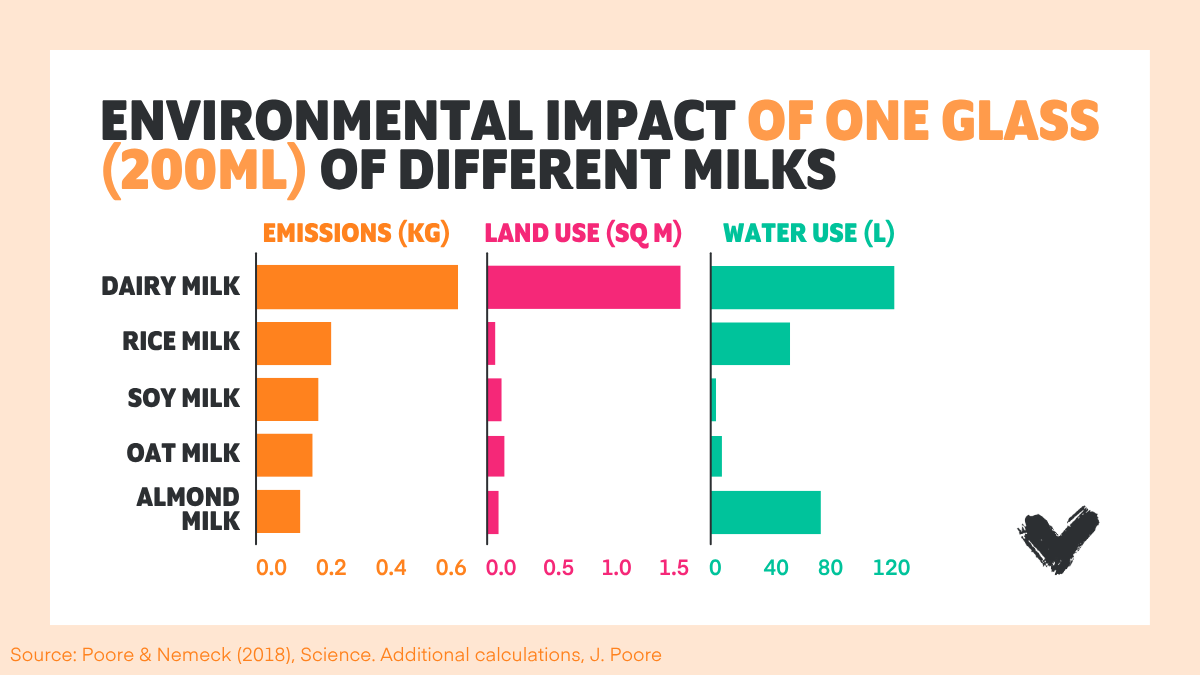

Environmental footprint

Research shows that cow’s milk has a significantly higher environmental impact than plant milks. A landmark study by Oxford University analysed the environmental impact of the most commonly eaten food products across 40,000 different farms in 119 countries. It found that the global carbon footprint of producing cow’s milk is three times higher than that of any plant milk. It also found that producing dairy requires times more land, and a great deal more water – a whopping 22 times as much as soya milk.14

One of the lead researchers, Joseph Poore, concluded:

“Avoiding consumption of animal products delivers far better environmental benefits than trying to purchase sustainable meat and dairy.”

Plant milk is the best choice for the environment – yes, even almond milk, which is a water-intensive option.

Animal suffering

Most animals farmed for food in the UK are reared intensively. Millions of pigs, chickens, cows and other farmed animals spend their lives in unhygienic, cramped and poorly ventilated conditions. The dairy industry is no different.

Like all female mammals, cows must be pregnant to produce milk, which they make specifically to feed their young. Instead of suckling for a year, their calf is taken away within 24 hours of birth so that humans can drink the milk – a separation which is traumatic for both the mother and her calf.

If the calf is female, she will be put through the same cycle of invasive artificial insemination, pregnancy, birth and separation. If male, he will be shot at birth and fed to hunting hounds, reared for low-grade beef or raised for veal either in the UK or abroad. The dairy industry won’t include this in their advertising campaigns. By choosing plant milks, we can stop this cruel cycle of abuse and suffering.

Conclusion

So, which is better: plant milk or cow’s milk? The reality is that while no option is perfect, plant-based alternatives require fewer resources to produce, have a smaller environmental footprint and eliminate prolonged animal suffering and abuse.

“While no plant-based dairy alternative studied in the report was directly comparable to dairy, this should not be considered in isolation but rather as part of a healthy, balanced, diet in which many foods contribute towards overall nutrient intake. It remains true to say that dairy is not an essential part of our diets and it is arguable whether dairy should be held as the ‘nutritional standard.”

Emily Angus, Senior Dietitian at The Vegan Society on the new government report

When fortified and combined with other plant-based food sources included in a varied diet, dairy-free milks can absolutely be part of a nutritionally complete and healthy vegan diet. The British Dietetic Association states that a well-planned plant-based diet is safe for people at all ages and life stages.15

References:

1. Mintel (2021). Sales of oat milk overtake almond. [online] www.mintel.com. Available at: mintel.com. Accessed 15 July 2025.

2. González-Montaña, J.-R., Escalera-Valente, F., Alonso, A.J., Lomillos, J.M., Robles, R. and Alonso, M.E. (2020). Relationship between Vitamin B12 and Cobalt Metabolism in Domestic Ruminant: An Update. Animals, [online] 10(10), p.1855. Available at: pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed 15 July 2025.

3. Wang, R., Bai, Y. and Yang, Y. (2022). Effects of dietary supplementation of different levels of vitamin B 12 on the liver metabolism of laying hens. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, [online] 102(13). Available at: pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed 15 July 2025.

4. E. Clegg, Miriam et al. “A Comparative Assessment of the Nutritional Composition of Dairy and Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives Available for Sale in the UK and the Implications for Consumers’ Dietary Intakes.” Food Research International, vol. 148, 1 Oct. 2021, p. 110586, sciencedirect.com. Accessed 15 July 2025.

5. The Vegan Society. “Calcium.” The Vegan Society, 2019, vegansociety.com. Accessed 15 July 2025.

6. Public Health England. “Vitamin D Supplementation during Winter: PHE and NICE Statement.” gov.uk. Accessed 15 July 2025.

7. Witard, Oliver C., et al. “Dairy as a Source of Iodine and Protein in the UK: Implications for Human Health across the Life Course, and Future Policy and Research.” Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 9, 10 Feb. 2022, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed 15 July 2025.

8. Alzahrani, Ali, et al. “Iodine in Plant-Based Dairy Products Is Not Sufficient in the UK: A Market Survey.” Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, vol. 79, 1 Sept. 2023, p. 127218, sciencedirect.com. Accessed 15 July 2025.

9. Dineva, M., et al. “Iodine Status of Consumers of Milk-Alternative Drinks v. Cows’ Milk: Data from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey.” British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 126, no. 1, 30 Sept. 2020, pp. 1–9, cambridge.org. Accessed 15 July 2025.

10. Kenneally, Sue, et al. “The Evidence Supporting a Plant-Based Diet for Optimal Health and Prevention of Chronic Disease.” Plant Based Health Professionals, plantbasedhealthprofessionals.com. Accessed 15 July 2025.

11. Harvard Health. “Lactose Intolerance.” Harvard Health, 2 Jan. 2019, health.harvard.edu. Accessed 15 July 2025.

12. NADIS. “NADIS Animal Health Skills – Part 5: The Impact of Mastitis and Lameness on Fertility.” Nadis.org.uk. Accessed 15 July 2025.

13. AHDB. “Somatic Cell Count, an Indicator of Milk Quality | AHDB.” Ahdb.org.uk, 2022. Accessed 15 July 2025.

14. Poore, Joseph, and Thomas Nemecek. “Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts through Producers and Consumers.” Science, vol. 360, no. 6392, 1 June 2018, pp. 987–992, science.org. Accessed 15 July 2025.

15. BDA (2021). Vegetarian, vegan and plant-based diet. [online] British Dietetic Association. Available at: bda.uk.com. Accessed 15 July 2025.