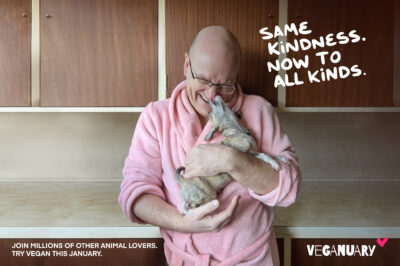

Veganuary’s Choose Chicken Free campaign aims to highlight the cruelty involved in the meat and egg industries. Evanna Lynch, actor and Veganuary ambassador, shares her experience of a typical British chicken farm.

It is 1 a.m. and I am miles away from my bed, crouched down behind a wall of trees in a pitch-black forest next to three masked men, speaking in barely audible undertones as we wait to enter a chicken factory farm.

It’s not my usual Saturday night excursion, nor my ideal first field trip since lockdown, and I can’t help but think of all the things I’d rather be doing at this moment: sleeping, reading a book, stroking a cat, watching footage of factory farms and telling people about how awful they are from a safe, comfortable distance – pretty much anything but entering one.

But I’m here because I’m convinced that factory farms are some of the worst places to exist and because I find it hard to believe they still do.

“Driving down the quiet, surrounding country roads admiring how bright the stars are away from the city glare, you would never know that 200,000 sentient beings are tucked mere feet away living lives of unending torment.”

You’d breathe in the fresh, cool night air and tell yourself that farms in the UK are humane, peaceful, open-air spaces and conveniently, the systems we pay to kill them have made it neatly possible to believe this fallacy.

So, when VFC invited me to go behind the doors of a factory farm to see the living conditions that 95% of chickens raised for slaughter in the UK endure, I felt sure it wouldn’t be as bad as the images burned into my brain from undercover investigations or documentary exposés, but I felt compelled to check.

‘Mark’, a full-time undercover investigator and expert on the specific rules, regulations and routines of factory farm life, who has already crept through this farm in the dead of night by himself, signals that the coast is clear and beckons for us to follow him out of the forest and into a chicken shed.

He waits in the forest himself as a lookout, armed with a walkie talkie and possessing a cool-headed composure that can only come from years of creeping stealthily through the most stressful places on earth.

He does this year-round, entering factory farms to expose the horrific conditions factory-farmed animals in the UK are raised in.

Later, I ask him do his parents worry about him doing the work he does and he tells me that his family don’t approve of his work, that it’s simpler when they just don’t talk about it. They find his views too radical, his chosen profession too extreme.

But the reality he’s exposing isn’t extreme; it is the industry standard.

Outside the chicken shed, Matthew, the founder of Veganuary and VFC, who has masterminded this excursion hands me and Chris, our cameraman, plastic blue protective suits and shoe protectors to put on.

‘For sanitary purposes – food safety regulations to keep the chickens clean’, he explains, and I detect a note of irony in his voice that I fully comprehend the moment we push open the door.

We stop and pause once through the door to look out at 25,000 chickens crammed together under one roof. You have to; it’s overwhelming. It’s chaos.

So many bodies squashed together in the one space, with no crates, no boxes, no shelter, no chance of a momentary reprieve from the utter havoc of thousands and thousands of scared, squawking chickens trampling all over one another.

It’s impossible to fathom that each of these white feathered bodies are individuals but look closer and you will see that they are. By my foot, one little chicken is pecking around my shoe eagerly, apparently oblivious to the danger my kind pose.

Another is attempting to preen his wing feathers even as his underside is soiled in faeces, maybe the saddest display of optimism I’ve seen all year.

I think of my cat who preens herself with the same conscientious precision, and of how much I’d fretted about leaving her in the care of a friend overnight.

It is strange, how deeply we look into the eyes of animals with fur and warm purrs appealing for ways to make them happy, and how easily we block out the desperate cries of those with feathers behind factory farm walls.

“So many bodies squashed together in the one space, with no crates, no boxes, no shelter, no chance of a momentary reprieve from the utter havoc of thousands and thousands of scared, squawking chickens trampling all over one another.”

There’s something I’ve neglected to tell the VFC crew; I am incredibly squeamish.

I don’t do well around dead animals. Even as a child long before discovering vegetarianism or veganism, the meat aisle always made me cry. I jump a mile when I see a chicken on her back, her skin red raw and featherless from the ammonia she’s been sitting in for weeks, her breath coming in ragged gasps.

She is hours from death, moments maybe. Matthew invites me to approach her and help her to her feet but I’m scared of her oozing wounds, her expression of abject suffering, so I hang back and watch as he carefully turns her onto her front and tries to help her to her feet, but she has no desire to get up again.

She gave up on life when she collapsed backwards into the ammonia-soaked dust at her feet, and why shouldn’t she?

She’ll probably have toppled back to where she was in a few minutes, Matthew says, explaining that chickens are bred at 4 times the rate they were in the 1950s and their legs are not biologically engineered to support their unnatural bulk.

We leave her, knowing she’ll be dead by morning, casually chucked in the bin, just a statistic, a life of pointless, private suffering.

Already, I just want to get to the end of this chicken shed and out the door where we can do something about it, and where we don’t have to stare these poor doomed creatures in the face.

I shuffle forward a few paces among the agitated chickens jostling around one another but every couple of feet they scatter to reveal more death and it only seems to get grislier with each step.

Even Matthew is finding it hard to stomach. ‘That is disgusting,’ he says, as he points to a chicken corpse that has been trodden flat into the floor, like a laminated anatomical diagram of a chicken that you might see on a poster at the vet. ‘That is like a horror film’.

I close my eyes for a moment, trying to gather myself standing in the centre of all these dead, dying and soon-to-be-dead animals, and I feel utterly lost, the kind of lost you feel when you’re 3 years old and lose sight of your mum in a giant supermarket and you look around in panic with the distinct sense that you’re too small to navigate this world, that you’ll never find your way back to safety.

How have we created this mess? How can we pretend that this is fine? How can we say ‘don’t show me that, you’ll ruin my chicken salad’ when your salad spent 6 long weeks in utter hell only for you to forget that you even ate a chicken salad by dinnertime?

There are some things, as adults, we have to look at. I open my eyes and force myself to look where Matthew is pointing at three chickens cannibalising another one who has entirely given up.

Her papery eyelids blink in slow motion as she looks directly up at the ceiling, as though she can see through it to the majestic blanket of stars, as other chickens peck and nip at her oozing sores, and I wonder does she know that the next bit will be peaceful and there’ll be no more pain.

“How can we say ‘don’t show me that, you’ll ruin my chicken salad’ when your salad spent 6 long weeks in utter hell only for you to forget that you even ate a chicken salad by dinnertime?”

‘Ok, I think I’m done’, I tell Matthew and Chris, after some time walking among the misery, trying not to step on the curled-up feet of the fallen birds, as if that makes a difference, and they nod grimly saying they’ll meet me outside.

They’re going to keep looking for a while, to try and capture more hidden lives of pain, to try and make their suffering less pointless by forcing other adults to take a look.

As soon as I shut the door of the chicken shed, I allow myself a sigh of relief. I pull off the awkward blue protective suit and an involuntary snort of laughter escapes me as I remember that we’d worn these out of a concern for cleanliness, to make sure we did not contaminate the piss, shit and disease-ridden chickens that would be served up to feed the nation.

I push open the door to the outdoors, the fresh night air a soothing balm, and suddenly the relief I feel is tempered by guilt because I am free to leave all that pain behind a heavy, soundproof door and the animals are not and there’s just something so unfair about that when they’ve done nothing at all to warrant such callous, systematic cruelty.

We trudge back through the forest, silently, and I look up at the stars, and I will always admire stars no matter the situation, but it’s unfair that those animals suffer and die in the dark, it’s unfair that we continue to subject them to lives of ceaseless misery when we have so many delicious, healthy alternatives to eating their flesh, when we know so much better now, and it’s unfair that the sky is so vast and peaceful and generous and that there are even more stars in the Milky Way than there are chickens in factory farms, but that those chickens will never get to see them.

We return to the hotel we’re staying at by 4 a.m. and I turn on my phone to find 11 missed calls and a flurry of panicked text messages from my mum, who I knew I should not have told about this particular excursion.

I text her back, assure her I’m fine, tell her she’s daft and that worrying only means you suffer twice and that there is already too much unnecessary suffering.

I am fine, I am safe, I was never in any danger, 3 fully grown men would have come to my aid if I’d so much as stubbed a toe, but nobody would save the chickens.

Nobody would know their pain or know them beyond a number. Nobody was worried that all of those little beings were in danger and nobody heard the cries they emitted all day every day of their short brutal lives.

“It’s impossible to fathom that each of these white feathered bodies are individuals, but look closer and you will see that they are.”

And nobody is heeding their cries of distress as an alarm bell signalling the dangers to come if we continue to allow these places to keep existing. Dangers like H5N1 bird flu evolved on factory farms and has a 60% death rate, and the fact that industrial animal farming has caused most new infectious diseases in humans in the past decade.

Dangers like deforestation because we import 3.3 million tonnes of soya every year and funnel 60% of it into the poultry industry.

Dangers like local wildlife and biodiversity being damaged by the chicken factory farms that pollute the surrounding rivers.

Dangers like tens of thousands of animals living in conditions that require antibiotics just to keep them alive, crammed together constituting a serious pandemic risk, in a system that uses more food than it gives back, driving deforestation and climate change, and all for a product we don’t need.

“It’s unfair that those animals suffer and die in the dark, it’s unfair that we continue to subject them to lives of ceaseless misery when we have so many delicious, healthy alternatives to eating their flesh.”

I climb into the pristine white hotel bed and send a prayer up that soon we dismantle this broken system and whisper in the dark to the chickens, who are long dead as I write this, whose successors, and successors’ successors are also dead, that I’m sorry.

But I know my words are meaningless and that every day we allow factory farming to continue we betray those chickens, the planet and ourselves and that we already know so much better and are blessed with the means to create and choose ethical, sustainable, healthy alternatives.

In the words of T. S. Eliot: “After such knowledge, what forgiveness?”